24 November 2023

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | ||||||

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | Re |

|

|

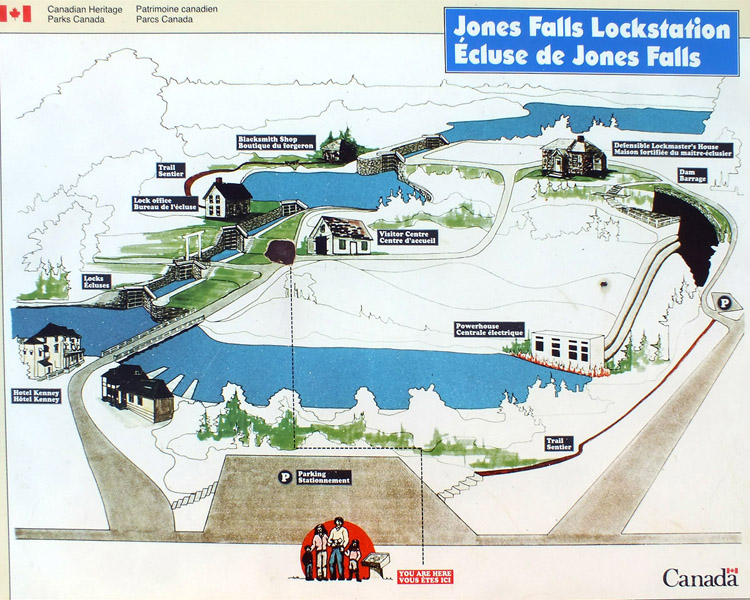

Friday 24 November 2023--I think it would surprise many of my fellow Americans to learn that the United States invaded Canada once, intent on annexing it by force. If we remember anything of what we were taught about the War of 1812, it's that we successfully defended our sovereignty in a "second war of independence." Canadian schoolchildren are taught that their ancestors successfully repulsed the American invaders. Thus both sides claim victory in a war whose only real accomplishment was a treaty that demilitarized the Great Lakes. I suppose all countries have righteous mythologies which their citizens do not like to be questioned. [As I edit this journal some weeks after my trip, a major political candidate is claiming that a country whose constitution, as originally written, explicitly condoned slavery has never been racist.] However you look at it, the fact is that relations between the US of A and British North America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were not always particularly cordial. It's in this context that the Brits, concerned about the vulnerability of supply lines along the St Lawrence River, decided that a secure water route away from the border was needed. The corridor chosen for a canal, up the Cataraqui River from Kingston and then down the Rideau River to the Ottawa River, followed a well-traveled First Nations trading route. It was surveyed in 1816, but for various reasons the project didn't get moving until 1826. Lieutenant-Colonel John By, the military engineer chosen to oversee construction, arrived at the mouth of the Rideau River in September of that year, and the following April he canoed the entire route to inspect the potential worksites. Remarkably, the Rideau Canal was built in five seasons, essentially finished by November of 1831. Even more remarkably, it stands intact today, the only 19th-century North American canal still operating complete on its original route, with virtually all of its original infrastructure. There are 49 locks (or 47, or 50--more on that later), numbered from Ottawa to Kingston. In the next few days, I will visit twenty of them at ten sites and learn much about this extraordinary engineering achievement, and the difficulties that had to be overcome to build it. My first stop today is Newboro, just ten minutes down the road from Westport. This is the height of land that separates the Rideau and Cataraqui watersheds. Colonel By must have been pleased to realize that dams at Chaffeys Mill and Poonamalie would raise Newboro and Big Rideau Lakes, respectively, to the same level, so that all that was needed to provide thirty miles of uninterrupted navigation was a canal cut a mile long, between the two lakes. Of course, the reason this is the watershed divide is because this short stretch of land is solid granite. Excavating the channel proved to be difficult, expensive, and time-consuming, and the swampy terrain was an incubator for the malaria that took its toll among the work crews. By decided that placing a lock at the Newboro end of the cut, and another across the waist of Big Rideau Lake, creating Upper Rideau Lake three feet above Newboro and Big Rideau Lakes, was less costly than digging the channel three feet deeper. Thus Upper Rideau Lake, upon whose shore Westport rests, is the crest of the canal. The canal's utility for military preparedness was never seriously tested, but it quickly became a commercial success. The railroads supplanted the canals, of course, but there was a period when they complemented each other--for some years, coal for the trains was brought up the canal from Kingston to Smiths Falls. But in the early years of the 20th century, the canal's main purpose shifted to pleasure boating, and so it remains today. Responsibility for the canal was handed over from the Department of Transport to Parks Canada in 1975. The former agency began a program of modernization in the 1960s, but fortunately, it hadn't gotten far. Newboro is one of three locks that got updated: its steel gates are opened and closed by hydraulic rams, powered electrically at the push of a button. Maintaining historical accuracy, insofar as it is possible, is now the park service's mandate; all of the other locks are operated by hand, by park staff, during the season. It's a short drive from Newboro to The Narrows, where a causeway separates Big Rideau Lake from Upper Rideau Lake. The lock here, like the one at Newboro, has a lift of about three feet; ten feet is typical. A blockhouse is testament to the strategic importance of the spot--it would have been easy for invaders to breach the causeway, making the canal impassable at Newboro. Colonel By proposed the construction of twenty-two such blockhouses along the canal, but only four were built, owing to budget concerns. A wooden swing bridge carries the modern road, built some time after the canal, across the channel just above the lock. Such bridges are themselves objects of historical interest, and wherever possible are maintained to appropriate specs. They are operated by the same park staff who work the locks, and some are said to be so well balanced that one person can push them open and closed. I'm off on a bit of a diversion now, to the village of Delta, twenty minutes southeast. There's an old mill here dating to 1810, reputedly the oldest stone flour mill in Ontario, now a museum (closed for the season, of course). In an early temperance sermon delivered here in 1828, Dr Peter Schofield claimed that "it is well authenticated that many habitual drinkers of ardent spirits are brought to their end by what is called spontaneous combustion." No one told me. An alternate route for the canal, called the Irish Creek route, was surveyed through here. It was a shorter path, avoiding the wide arc of the Rideau Lakes, but lacked sufficient water for operation--the proposed remedy, a long supply canal from Big Rideau Lake, was not deemed practical. Had the canal been built through here, the mill would have been torn down, as many were along the canal. Colonel By had full powers of expropriation, and landowners along the way could only argue about the amount of compensation they were due. I mosey across the street to have a cup of coffee at the Bastard Coffee House. Truth be told, it was finding this name on the map that drew me here. Delta was once part of Bastard Township, probably named for British MP John Pollexfen Bastard. No lie. The name lives on here and there, mainly in road names, but also on this one business. The proprietors perhaps thought it would draw curious tourists with juvenile senses of humor. Had I not been one such, I'd never have learned that I was at risk of spontaneous combustion. Another twenty minutes south and west, I come back to the canal. Jones Falls might be the most impressive piece of engineering on the entire route. The stone arch dam at the top of the site is a bit lost in the landscape today--it's not even visible from below--but it doesn't take much imagination to realize what an extraordinary structure it was for the time. At 60 feet, it was the highest dam in North America. The stone was drawn by oxen from a quarry six miles away. The dam floods a ravine a mile long, with a drop of 59 feet. There were originally meant to be six locks, each with the usual ten-foot drop, but early in the planning process, Colonel By realized that the 108-foot length of each lock, tailored for the expected barge traffic, would be insufficient for steamboat travel, an industry then in its infancy. Thus all of the locks on the canal are 133 feet long. It's undoubtedly due to By's foresight that the canal did not face a prohibitively expensive refurbishment, or, more likely, abandonment, in the following decades, as happened to so many others. But the increased length presented a problem here. As at several other sites, the locks were built in a snie, a dry flood channel, adjacent to the current watercourse. There was only so much room. By redesigned for four locks, each with a fifteen-foot lift, which was considered extreme, and which necessitated particular care in construction. An early road passed over the canal, but a modern bridge a mile and a half upstream rendered it obsolete. The footings of a swing bridge are still visible on either side of one of the locks. Without through traffic, Jones Falls is a peaceful spot. The Hotel Kenney, built in 1888 below the locks, looks like it would be a nice place to spend a couple of quiet evenings. It's evident from scaffolding that work is being done on the upper lock, and as I walk back to my car, I happen to catch one of the workmen as he is knocking off for the day. He tells me that the masonry in each lock has to be disassembled and rebuilt occasionally. This is done when the canal is closed in winter, under a heated tent. It's not until I'm driving back to Westport that it occurs to me to ask him how often this needs to be done, and a thousand other questions. Next |

Newboro, Narrows, Jones Falls

|

The Cove Country Inn

|

Newboro, #36

|

Newboro

|

Canal Cut

|

Newboro

|

Newboro

|

Newboro

|

Blockhouse, The Narrows

|

The Narrows, #35

|

Swing Bridge, The Narrows

|

The Narrows

|

The Narrows

|

Route 42

|

Delta Mill

|

Bastard Coffee House

|

Bastard Coffee House

|

Bastard Coffee House

|

Stone Arch Dam, Jones Falls

|

Stone Arch Dam

|

Jones Falls Lock Office

|

Stone Arch Dam

|

Stone Arch Dam

|

Hotel Kenney, Whitefish Lake

|

#42

|

#41

|

#41

|

#41

|

#39

|

Jones Falls

Next

| November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | ||||||

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | Re |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary

MrTattieHeid1954@gmail.com