26 November 2023

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | ||||||

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | Re |

|

|

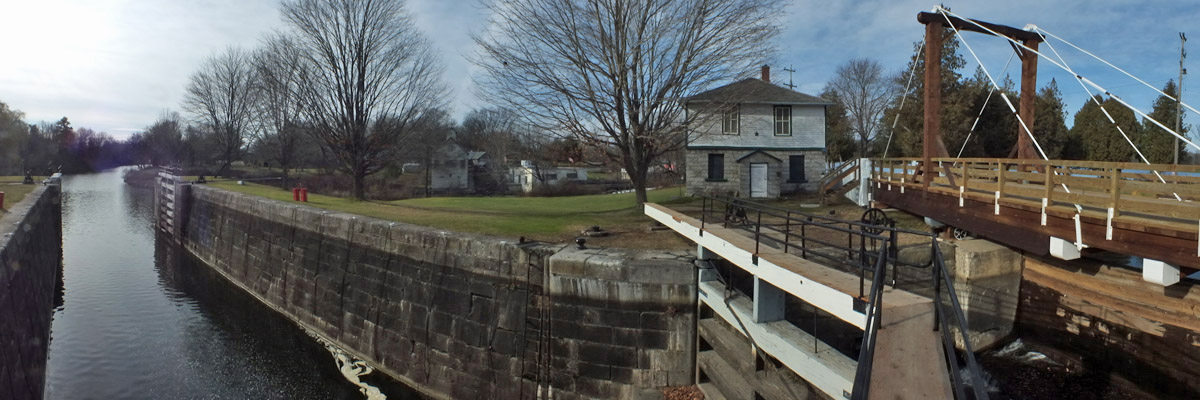

Sunday 26 November 2023--Check out of the Cove Inn and leave Westport, promising to myself to return someday. Stop at the large gas station just outside town to put a small amount of fuel in the car, just enough to get me back across the border tomorrow. Their coffee machines are out of order, both of them, which is vexing. They might as well be out of gasoline. East on route 42 I go, then south on broad and fast route 15, toward Kingston. I'll see the last few canal locks to the south on the way. First is the pair at the station now called Brewers, formerly Upper Brewers. This was named not, alas, for a brewer, but for a John Brewer, who built mills here. (I suppose I should be happy that no breweries were harmed in construction of the locks.) Colonel By purchased these, meaning to put locks in the main channel. He changed his mind, raising the dam above the mills and digging a short canal cut to the west. The mills were left standing, but were closed by 1845. What is more interesting than the locks here, perhaps, is how water was managed upstream. The main flow out of Jones Falls originally turned northeast, toward present-day Delta, and into the Gananoque River. South of the bend was a very large bog, which drained into both the Gananoque and Cataraqui watersheds. Mill activity at the site of the current hamlet of Morton in the early years of the 19th century caused the bog to flood and drain mainly into the latter river. Dealing with the bog was a problem for Colonel By, solved mainly by flooding it further, with the dam at Upper Brewers and another above Morton. (The latter includes the waste weir for this section of the canal, so that the water for navigation goes down one river, and the overflow goes down the other.) Even then, making the newly-created Cranberry Lake navigable involved the removal of a lot of drowned trees, as well as countless islets of vegetation that tended to dislodge and clog the route. This work was made particularly unpleasant by a stench reminiscent of "a cadaverous animal in the last stages of decomposition" coming from the disturbed mud. The tree work, at least, could be done in winter, mitigating the odor issue to some extent. John Brewer also built mills two miles downstream, at a site called Lower Brewer's Mills, now labeled Washburn. At the time of the canal's construction, these mills were operated by a Colonel McLean. By placed a lock in a canal cut that bypassed a sharp bend in the stream, allowing the mills to remain intact. McLean was nevertheless unhappy with the project, and went so far as to flood the works several times, forcing By to post guards. He eventually was obliged to buy McLean out. One might conclude that the disagreeable fellow had cursed the site, for it proved to be the most troublesome lock on the canal. The fact of it is that it was built rather hastily on a poor foundation, which was leaky from the start. A complete rebuild was recommended as early as 1840, but funding was not forthcoming. A wall collapsed in 1861. There were numerous partial reconstructions, and constant repair for over a century. The lock was finally completely rebuilt in 1977. Looks good and solid to me. Ten miles along is the last lockstation on the canal (or the first, if you're coming from Lake Ontario), Kingston Mills. The Cataraqui dropped twenty feet here, and the British government built saw and grist mills in 1784, in support of the Loyalist settlement a few miles away, at present-day Kingston. The plan here was for three locks, with two more at gentler drops upstream. As he did so often, By improved the original plan on the fly, raising the dam and installing a fourth lock here, which flooded the route to navigable depth all the way up to Washburn. Embankments containing the raised body of water extended a thousand yards in either direction from the dam. The road passing over the upper lock was, at the time, the main route from Toronto to Montreal, and the bridge has been updated several times. The 401 crosses the river less than a mile to the south, just out of sight. A wooden truss bridge was built above the flight of three locks for the Grand Trunk Railroad in 1853, replaced in 1929 by the steel bridge that serves Canadian National to this day. The Via Rail train to Toronto passes overhead as I wander the site. The body of water that drowned the swamp above Kingston Mills is now called Colonel By Lake, a salute to the man whose achievement was well appreciated by the residents of the land he helped to transform. No such tributes were forthcoming in London, where his expenditures came into question when he returned in 1833. The cost of the canal had escalated considerably, as usually happens with such projects. But he kept careful accounts, and there was nothing that could have been considered improper. Moreover, By's orders had given him substantial leeway to exercise his judgment, which he did in admirable fashion, frequently avoiding greater costs by making substantial changes. There were never any charges made against him, but no one spoke up in his favor, either. It seems he was the victim of politics--there had been an election, and the new government was keen to paint the former regime as spendthrift. By was retired, and he died in 1836 at age 53, his name still under a cloud. I drive into Kingston and get in the queue for the ferry to Wolfe Island, where I'm spending my last night on this trip. There are lovely views of the city on the way over, and the Martello towers and other fortifications that protected the approach to the Rideau Canal from those nasty Americans in the first half of the nineteenth century. Somebody somewhere--the bartender at Lake on the Mountain, probably--told me, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that Wolfe Island is famous for wind turbines, and I can see that there are lots of them. I arrive a little too early to check into the Hotel Wolfe Island in downtown Marysville (pop ~400), so I drive off to the western end of the island and catch the ferry to Simcoe Island (pop ~80). Out at the western end of the dirt road that runs the length of the island, I have a look at the lighthouse at Nine Mile Point, which dates to 1833. The nearby keeper's residence is privately owned, I suppose used as a holiday cottage; I see no signs of life there just now. Back I go to Marysville, where I check in, contactless again. I'm not really sure what to expect here, but my room turns out to be spacious and comfortable. There is obviously some renovation and upgrading going on. The restaurant and bar are a pleasant surprise, as well, reasonably lively for a Sunday night in such a small place. There is entertainment, a Celtic harpist, of all things, and decent beer to drink. I haven't left myself any time to explore the island, which, at eighteen miles long and six wide, is the largest of the many that lie in the first miles of the St Lawrence. I'm not sure there's really anything to see, apart from farmland and wind turbines. But I know there's a decent place to stay, and I think it might be worth another night sometime. Next |

Brewers Mills, Washburn, Kingston Mills, Wolfe Island

|

Route 15

|

Brewers Mills, #44

aka Upper Brewers

|

...and up to...

|

Brewers Mills, #43

|

Washburn

aka Lower Brewers

|

Washburn, #45

|

Washburn

|

Washburn

|

Washburn

|

Washburn

|

Washburn

|

Kingston Mills Dam And Blockhouse

|

Kingston Mills Turning Basin, #46 At Right

|

Kingston Mills, #47

|

#47

|

#48

|

#49

|

#49

|

#48 And Railroad Overpass

|

Wolfe Islander III

|

Kingston

|

Kingston

|

Royal Military College Of Canada

|

Cathcart Tower

|

Wolfe Island

|

Simcoe Island

|

Simcoe Island

|

Nine Mile Point Lightouse

|

Nine Mile Point

|

Nine Mile Point Lightouse

|

Simcoe Island

|

Wolfe Island From Simcoe Island

|

Simcoe Island Ferry

|

Road To Marysville

Next

| November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | ||||||

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | Re |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary

MrTattieHeid1954@gmail.com